Incoterms stands for International Commercial Terms. These are published by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and describe agreed commercial terms. These rules set out the responsibilities of buyers and sellers for the supply of goods under a contract. They are very commonly used in cross-border commercial transactions in order that both sides in a transaction are aware of the contractual position. They help businesses avoid costly misunderstandings by clarifying the tasks, costs and risks involved in the delivery of goods from sellers to buyers. The latest terms were published in 2010 and came into effect in 2011.

The use of Incoterms for assistance for VAT purposes

One of the most difficult areas of providing VAT advice is obtaining sufficient detailed information to advise accurately and comprehensively. Quite often advisers are given what a client believes to be the arrangements for a transaction. This may differ from the actual facts, or the understanding of the other party in the transaction.

Pragmatically, this uncertainty about the details may be increased if; a number of different people within an organisation are involved, it is a new or one-off type of transaction, there are language difficulties, or communication and documentation is less than ideal. In such cases, incoterms will provide invaluable information which gives clarity and certainty and usually give a sound basis on which to advise. This enables the adviser to establish the place of supply (POS) and therefore what VAT treatment needs to be applied.

So what is this set of pre-defined international contract terms?

They are 11 pre-defined terms which are subdivided into two categories:

Group 1 – Incoterms that apply to any mode of transport are:

EXW – Ex Works (named place)

The seller makes the goods available at their premises. This term places the maximum obligation on the buyer and minimum obligations on the seller. EXW means that a buyer incurs the risks for bringing the goods to their final destination. The buyer arranges the pickup of the freight from the supplier’s designated ship site, owns the in-transit freight, and is responsible for clearing the goods through Customs. The buyer is also responsible for completing all the export documentation.

Most jurisdictions require companies to provide proof of export for VAT purposes. In an EXW shipment, the buyer is under no obligation to provide such proof, or indeed to even export the goods. It is therefore of utmost importance that these matters are discussed with the buyer before the contract is agreed.

FCA – Free Carrier (named place of delivery)

The seller delivers the goods, cleared for export, at a named place. This can be to a carrier nominated by the buyer, or to another party nominated by the buyer.

It should be noted that the chosen place of delivery has an impact on the obligations of loading and unloading the goods at that place. If delivery occurs at the seller’s premises, the seller is responsible for loading the goods on to the buyer’s carrier. However, if delivery occurs at any other place, the seller is deemed to have delivered the goods once their transport has arrived at the named place; the buyer is responsible for both unloading the goods and loading them onto their own carrier.

CPT – Carriage Paid To (named place of destination)

The seller pays for the carriage of the goods up to the named place of destination. Risk transfers to buyer upon handing goods over to the first carrier at the place of shipment in the country of Export. The Shipper is responsible for origin costs including export clearance and freight costs for carriage to named place (usually a destination port or airport). The shipper is not responsible for delivery to the final destination (generally the buyer’s facilities), or for buying insurance. If the buyer does require the seller to obtain insurance, the Incoterm CIP should be considered.

CIP – Carriage and Insurance Paid to (named place of destination)

This term is broadly similar to the above CPT term, with the exception that the seller is required to obtain insurance for the goods while in transit. CIP requires the seller to insure the goods for 110% of their value.

DAT – Delivered At Terminal (named terminal at port or place of destination)

This term means that the seller covers all the costs of transport (export fees, carriage, unloading from main carrier at destination port and destination port charges) and assumes all risk until destination port or terminal. The terminal can be a Port, Airport, or inland freight interchange. Import duty/VAT/customs costs are to be borne by the buyer.

DAP – Delivered At Place (named place of destination)

The seller is responsible for arranging carriage and for delivering the goods, ready for unloading from the arriving conveyance, at the named place. Duties are not paid by the seller under this term. The seller bears all risks involved in bringing the goods to the named place.

DDP – Delivered Duty Paid (named place of destination)

The seller is responsible for delivering the goods to the named place in the country of the buyer, and pays all costs in bringing the goods to the destination including import duties and VAT. The seller is not responsible for unloading. This term places the maximum obligations on the seller and minimum obligations on the buyer. With the delivery at the named place of destination all the risks and responsibilities are transferred to the buyer and it is considered that the seller has completed his obligations.

Group 2 – Incoterms that apply to sea and inland waterway transport only:

FAS – Free Alongside Ship (named port of shipment)

The seller delivers when the goods are placed alongside the buyer’s vessel at the named port of shipment. This means that the buyer has to bear all costs and risks of loss of or damage to the goods from that moment. The FAS term requires the seller to clear the goods for export. However, if the parties wish the buyer to clear the goods for export, this should be made clear by adding explicit wording to this effect in the contract of sale. This term can be used only for sea or inland waterway transport.

FOB – Free On Board (named port of shipment)

FOB means that the seller pays for delivery of goods to the vessel including loading. The seller must also arrange for export clearance. The buyer pays cost of marine freight transport, insurance, unloading and transport cost from the arrival port to destination. The buyer arranges for the vessel, and the shipper must load the goods onto the named vessel at the named port of shipment. Risk passes from the seller to the buyer when the goods are loaded aboard the vessel.

CFR – Cost and Freight (named port of destination)

The seller pays for the carriage of the goods up to the named port of destination. Risk transfers to buyer when the goods have been loaded on board the ship in the country of export. The shipper is responsible for origin costs including export clearance and freight costs for carriage to named port. The shipper is not responsible for delivery to the final destination from the port (generally the buyer’s facilities), or for buying insurance. CFR should only be used for non-containerised sea freight, for all other modes of transport it should be replaced with CPT.

CIF – Cost, Insurance and Freight (named port of destination)

This term is broadly similar to the above CFR term, with the exception that the seller is required to obtain insurance for the goods while in transit to the named port of destination. CIF requires the seller to insure the goods for 110% of their. CIF should only be used for non-containerised sea freight; for all other modes of transport it should be replaced with CIP.

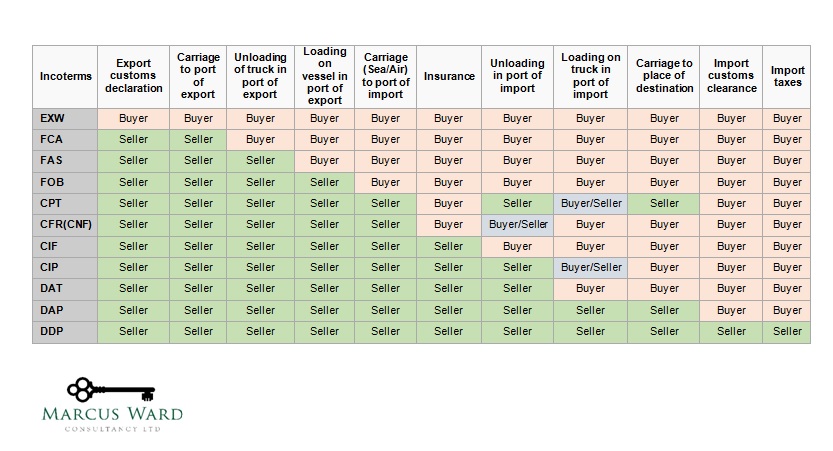

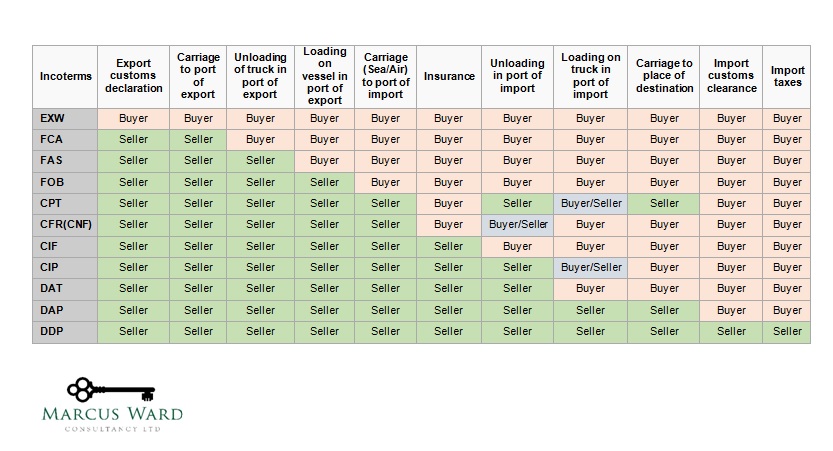

Allocations of costs to buyer/seller via incoterms

Summary Chart